Learn to Transform Pain into Art - Still Writing by Dani Shapiro

The post below belongs to a series of articles about my personal journey in finding teachers and mental renewal in good literature.

If you wonder why learning from good literature is essential, find out more in "A Good Read"

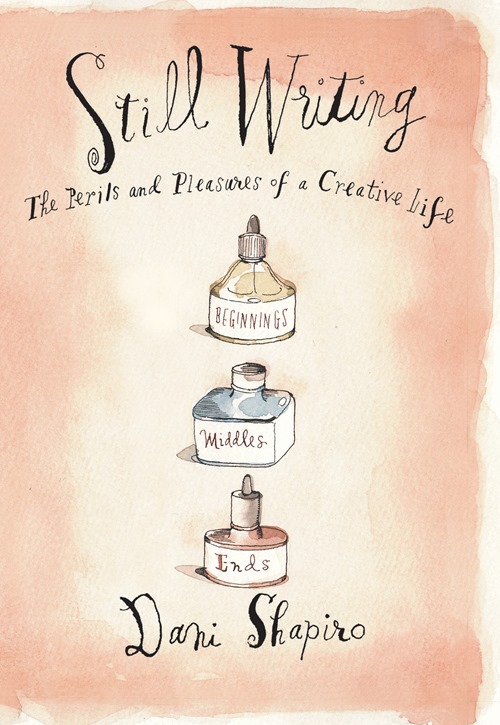

Dani Shapiro is an American novelist and memoirist, who I got to know of by reading her genuine article featured on The New Yorker, titled “A Memoir is not a Status Update”. This article compelled me to find her website and read her book “Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life”- the first book I ever read on the topic of writing.

What shines through Shapiro’s book is how she transformed her pain into stories. These stories are woven on the page like a painting made of spider silk, of which the colors are tender, poignant, and soft. These stories are told not only from the narrative of a published writer, but also intertwined the voice of a lonely daughter, a trembling mother, and a vulnerable woman.

“Only child” and “older parents” is the corner from where she begins piecing together the jigsaw puzzles of her childhood. Shapiro was born in a Jewish family, where she described “on the Sabbath, from sundown on Friday evening until sundown on Saturday, we didn’t drive; we didn’t turn on lights, or the radio, or television. I wasn’t allowed to ride my bike, or play the piano, or do homework”. Every facet of the real world that surrounded her childhood was soundless, dull, and bleak - especially her parents’ marriage, of which the suppressed silence was loud enough for Shapiro, an ever so sensitive girl, to hear. This childhood, as she wrote, “isn’t a prerequisite for a writing life, of course, but it certainly helped.” She strained to hear beyond this muted reality to find something, anything that wasn’t sad or fruitless. When she turned eleven or twelve, she started locking herself in her room to write and set herself free. She began to become a writer.

Shapiro woke up one day in the portrait of “a twenty-three-year-old college drop-out trying to disengage myself from my married boyfriend, subsisting on a diet of white wine and scotch and saltines”. There she found herself in the daylight nightmare of her parents’ car accident, which took away her father in two weeks and put her mother on wheel chair until she died few years later. As she was sliding down a self-destructive spiral made of depression, alcoholism, drug abuse, and a vexing relationship with a married criminal man, that accident stormed in, ironically, as the right condition – as she described – for “the blooming of an orchid or the metastasis of a tumor”. In her memoir, “Slow Motion”, she writes down her grief and writes herself in and out of her pain. “I was broken open, no longer innocent or oblivious. I had a story to tell - a story I was not necessarily ready to tell, but that didn’t matter.”

“My life closed twice before its close”, Shapiro quoted Emily Dickinson. She couldn’t have yet imagined how a life could close twice until the moment her six-month-old Jacob was diagnosed with Infantile Spasms – a rare disorder that leaves severe impairment on surviving infants, whose luck is only fifteen percent. There her life closed once more. She often wrote to pick her up from pain, but this time, it was different. She mentioned Joan Didion’s words, “Against life’s worst onslaught, nothing avails, not even art. Especially not art.” Standing in front of the crib of her child, watching him drink down the medicine that was not was not going to save him at three o’clock; she was a writer who couldn’t write. A part of her died, and it took one year to come back to life as her son began to heal. She started writing a novel about maternal anxiety, from the darkest, most terrified and shattered place inside of her. In that place, she realized that “fighting it was futile, impossible. Accepting, even embracing this, was the true work, not only of being a writer, but of being alive.”

The last notable narrative that transcends this “how-to-write” book is of a tender woman Shapiro, whose quiet perseverance was illuminated by her own vulnerability. She admits to be no risk taker, “not in the physical sense”. But when she is alone in a room, she is “compelled to take risks”. As a published author, she taught me that creativity is an act of good faith, that if I keep showing up for my part of the process, with patience and diligence, something will come, piece by piece. She taught me to have a different kind of ambition: the creative kind. This kind of ambition must not urge us to seek fame or money or power. It obliges us to face ourselves on the page, with a “desire to get it right, and the suspicion that there is no getting it right”, in a process where there’s no room “for an overblown ego”. She taught me to write in the face of tragedy, at both the love and the fear of losing the beloved, and even when life one day makes me handicapped - continue to write anyhow. She wrote:

“It is our job, our responsibility, perhaps even our sacred calling, to take whatever life has handed us and make something new, something that wouldn’t have existed if not or the fire, the genetic mutation, the sick baby, the accident. To hurl ourselves in an act of faith so complete that our fears, insecurities, hopelessness, and despair blur along the edges of our vision. We stop for nothing.”

I reached the end of “Still Writing” knowing that what I had just read wasn’t in any way a simple “how-to” book in the discipline of writing. Through her book, Dani Shapiro not only taught me how to be a writer but also how to be human, to heal myself through art, and to “stop for nothing”.