Walt Disney’s first Neverland: the Courage to Begin and the Grit to Stand up from Failure

The Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was the first cartoon I ever saw. For a 4-year-old, it was the only thing better than sundae ice cream. I made my mother played it as many time as our old videotape could handle. My childhood was made of fairies, princesses, princes, beasts, magic creatures; and like many other kids, perhaps you too, whenever I look back to all these years with longing, I find Walt Disney’s creation – though by that time I didn’t know it was a name of a man.

Though Walt insisted that he did not make movies for children, his creation and legacy have put a touch of fantasy in the hearts of millions of kids. For me, that touch is so resonant that hearing the movies’ titles - Dumbo, Pinocchio, Bambi, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Alice in Wonderland… – is enough to tickle my heart with a little joy and hope. Is it just me, or do you feel the same?

When I was suggested to write about Walt Disney for The Grand 20-Somethings, I was thrilled. It turned out, Walt’s story was no less magical than the animation he created.

He did not have a suit of his own, only a pair of loud threadbare black-and-white-checked trousers, a checkered jacket, a gabardine raincoat, and an old brown cardigan. His suitcase was frayed cardboard, half of which was packed not with clothes but with animation equipment an his only extravagance was a five-dollar pair of Walkover shoes he had bought with the money from the sales of the camera.*

That day Walt Disney was 21, boarding a train to leave Kansas. He took a last look at the city where he’d trudged through darkness and biting snow as a paperboy to help his family earn a living for 6 years; where he’d stood up to his father aggression; where he’d immersed in drawing to find his escape and began to work as a cartoonist; where he’d attempted and failed in an illustration business and then found his passion in animation; where he’d opened his first animation studio only to see it went to bankruptcy 1 year after.

In debt with many investors, no money in his pocket, as thin as a tuberculosis patient after nights with restless sleep in the studio and days scavenging left-overs from restaurants. There was nothing in Kansas for Walt. With all the bruises of the lost fight, now he needed to begin again. Walt would leave for California.

Walt Disney was nevertheless strangely delighted: “It was a big day, the day I got on that Santa Fe, California Limited… free and happy…as if …were lit up inside by incandescent lights.”

Whenever life kicked him hard in the stomach, he would find away to run, walk or crawl ahead. Not only he did it this time, he would do it again and again and again. This was Walt Disney’s way to claim his 20s and his life: keep forging ahead no matter what life threw at time, and do so with a happy tune in each footstep.

Walt Disney was the real Peter Pan, the boy who stays forever young. Walt was called “naïve, joyful, innocent-seeming, peculiarly positive, unbelievably optimistic”. If Peter Pan has Neverland; Walt Disney had his animation studio. In there, he could create his own world – an imagined reality which is immune to the laws of physics and logic. With this godlike power, Walt expressed his own truths about humanity: that fun and melodies and love matter; that good will prevail; that no matter how small you are, your big dreams are valid. This was his voice, Walt Disney’s voice.

Great artists know that the best way to find their voice is to use it. Walt was one of them. He used his voice with a strong sense of urgency, and without any hesitation. Walt did not wait around to get ready. He did not postpone until he had 100% of the plan. He was a go-getter who did not know where he was getting to, only that he would get somewhere.*

Walt Disney once he found what tickled his heart, simply chose to begin.

“But now I don’t have ___(fill in the blank with experience/money/people)” was never his excuse. Walt knew early that he was too independent to work under someone else’s command. Walt also knew that animation in 1920s was in its infancy , and his vision for it was too revolutionary, because of that fawning over the big guys was useless because they were the ones with the biggest steak in the status quo.

Walt Disney’s first Neverland was the Laugh-O-Gram. Walt founded the company when he was 20. Laugh-O-Gram were with little funding, no proper animation equipment, zero distributor, and none of its people knows much about animation, Walt Disney included. Walt scraped money from investors, acquaintances, family, friends. He and his staff learnt as they went, from the few animation books that existed, and even fewer contemporary animations. They improvised their equipment. But because of starting so innocently, they did things that animators almost never did just because the experts were attached to doing things in a certain way. Most importantly, they were kids having a great time.

A friend who visited Walt’s office at the time asked if he was making any money, “he smiled and said, No, but he was having fun. Again I thought, Will he ever grow up?” Another person described Walt in those days as having “the drive and ambition of ten million men.”

The young and inexperienced Walt Disney had not only the courage to begin, but also the determination to endure and the grit to stand up from failures.

Though the Laugh-O-Gram creation was the best in its class, finding distributors were tough because it was too revolutionary. Thus, all of Laugh-O-Gram’s hope hung onto one deal. They worked with no advance payment for months. But their client, right before the due date, went bankrupt. Walt didn’t surrender his hope. He labored to find other distributors. No success.

Once again, running out of money and alternatives, Walt ignored those calamities and did what no other businessman in their right mind would do – because he wasn’t a businessman. He enthusiastically attempted another series that might crack the market. In that desperation, his light bulb lid, that’s how Alice’s Wonderland was born – the first ever animation with human entering the cartoon world and interact with cartoon characters.

By then all the staff had left, so Walt ended up doing the entire project by himself. He was groping. “When my credit ran out I was tempted to go and eat, order my meal and tell them I couldn’t pay,” Walt recalled. “But I didn’t have the nerve. I was so damn hungry.” He slept on rolls of canvas and cushions in the office, took a bath once a week at Union Station. Despite all that, Walt failed to save Laugh-O-Gram and his first Neverland shattered.

What is so astonishing about Walt Disney is that “he was always optimistic…about his ability and about the value of his ideas and about the possibilities of cartoons in the entertainment field. Never once did I hear him express anything except determination to go ahead,” his colleague remembered. Even the attorney who handled the bankruptcy exclaimed: “Most people filling for bankruptcy are disturbed or bitter. Walt wasn’t! ” It was as if Walt lived him his animation world where even psychological laws could be suspended. “He was confident, beyond any logical reason for him to be so,” wrote his biographer.

However, Walt’s heart was not made of diamond. Walt was “crushed and heart-broken” for the failure and disappointment of so many who had trusted in him and had lost money for their trust: “that first big setback got me right down and out.” However, what set Walt apart from other 10 millions man was that he sincerely believed the Laugh-O-Gram bankruptcy had made him tougher, more determined, and inured to failure.*

This was an incredible attitude for someone so young. Almost 100 years have passed since his time, I think this should be the attitude for all 20-somethings out there: once you find what make your heart tickled, dare to begin. Dare to confront the seemingly-sensible excuse: “I need to work for XYZ to gain more experience/money/network”. There is another option for the independent-minded ones who are – like Walt Disney – dreaming of creating something insanely great of your own: you are enough to begin.

When we are faced with setback, we can tell ourselves two stories. A limiting story “This is not for me. I’m not good enough. I’d better do something else.” Or a growth story “This failure made me become more! Now I’m better prepared to succeed.”

A failure can be horrible or glorious. It’s entirely up to the story we choose. I once heard from a very wise person that “It doesn’t matter what we believe, but what we choose to believe.” Walt Disney chose to believe in fairy tale, every single times.

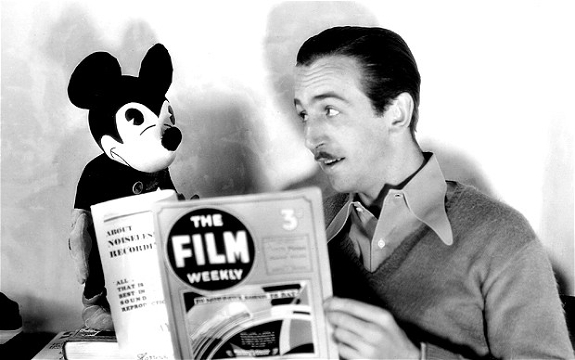

Throughout Walt 20s, and for the rest of his life, his greatest creations born out of desperation, like a beautiful lily shooting out from the mud. Mickey Mouse was created when Walt was at the verge of losing the entire studio again at the age of 26. Then in a garage with few of his loyal animators, Walt thought of putting sound in the Mickey series, invented the world’s first animation with sound, revolutionized the entire industry.

Walt Disney was a normal 20-something with gifts and flaws like all of us. What made his 20s and his life so grand? Because Walt Disney knew how to tell stories, not only to millions of people through animations, but also to himself.

When You Wish Upon a Star is the anthem of Walt Disney studio. It was also the background song of Walt’s life. I imagine Walt Disney in his 20s - with his self-painted mustache so that he could look old enough to be taken seriously, in his old brown cardigan, and a second hand Universal camera in his hands – walking the streets of Kansas - where it all began, and sang:

“When you wish upon a star

Makes no difference who you are

Anything your heart desires

Will come to you

If your heart is in your dreams

No request is too extreme

When you wish upon a star

As dreamers do

Fate is kind

She brings to those who love

A sweet fulfillment of their secret longing

Like a boat out of the blue

Fate steps in and sees you through”

*Walt Disney by the talented biographer Neal Gabler is a wonderful read and re-read. I strongly recommend this book, and am grateful for having this book as reference to write this article.