Mahatma Gandhi’s 20s: from an Undistinguished Schoolboy to a Political Leader

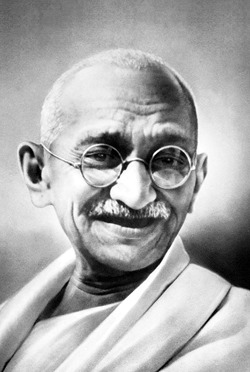

When we think of Mahatma Gandhi, we often picture a thin man with a humble smile; under his fragile figure lies inconceivable tenacity; and behind the round spectacles, tinkling in his eyes the love for humanity. This is the Mahatma we all know: leader of Indian freedom struggle; father of non-violent resistance movement; bridge-builder across races, faiths and nations. However, little do we know about Mohandas K. Gandhi – the Gandhi before India, the Mohandas before the Mahatma.

September 1888, 1 month before his 20th birthday, Gandhi sailed to London to study law; 3 years in London – for the first time, he experienced community activities, international friendship, journalism and spiritual studies; 22 years old, after his graduation, Gandhi returned to Bombay; 24 – he landed in South Africa alone and began his career as a lawyer in a strange land; 25 – he wrote his first petition for Indian rights became secretary of Natal Indian Congress; 26 – Gandhi published the first pamphlet; 27 – he brought his family South Africa; 28 – he endured the first physical attack as the result of his cause.

For Mohandas Gandhi, his 20s was the defining decade. This decade shaped him as a social reformer, a community leader, a political thinker, a family man and a spiritual pluralist. Mohandas Gandhi claimed his 20s in his own way. I hope that his story will inspire you to claim your 20s your way.

What was the Mahatma made of?

Second half of the 19th Century, India’s peninsula, orthodox Hindus, conservative middle caste family - that’s the context in which Mohandas K. Gandhi was born. There was nothing particularly distinguished about Gandhi’s academic achievement. In fact, his early school years’ record was rather discouraging: spotty attendance; lower half, and at times, almost bottom of his class; distracted by his father’s illness, and early marriage. 19 years old, Gandhi enrolled for BA degree, but his first semester was mediocre. He committed to an arranged marriage at the age of 13. He fulfilled his piety at home. He wasn’t too bad at school. He made his wife pregnant, eat vegetarian meals, read books, hung out with friends, took examinations. Mohandas Gandhi before his 20s was a typical Indian middle-class educated young man.

Gandhi was very different from Albert Einstein’s early independent thinking and imagination, or Steve Jobs’ unruly behaviors and irresistible charisma. At first glance, nobody would expect 19-year-old Mohandas K. Gandhi to some day become the Mahatma of not only India but also the world. Yet, if Albert Einstein’s face has become the symbol of genius, Steve Job’s portrait the icon of innovation; Mohandas Gandhi’s image has become the synonym of peace, faith and humanity.

How?

Something noteworthy about the life of Mohandas Gandhi is that he was never the man of great ambitions. In the first 30 years of his life, he had never had a lofty aspiration to fight for his countrymen through a politics career. Neither did he anticipate that he would become a community leader, nor did he expect himself to inspire anyone. All he had wanted was an honest, useful life. The young man Gandhi was simple, grounded and benign like a loaf of fresh bread.

He was too kind to impose on people, too shy to deliver speeches sometimes, too simple-minded to have a career plan, let alone planning for a revolution. Mohandas Gandhi was shaped and forged largely by the circumstances and the happenstances in which he found himself. It was the force of history that transformed him to a Mahatma.

However, unlike wild flowers growing undirected, Gandhi grew in his natural directions. Because he was rotted in his changeless characters: an immense curiosity, an uncompromising integrity, and a humanitarian conviction.

The first daring act

19 years old, after the first so-so semester of his BA degree, Gandhi heard the idea of studying law in England. According to a family friend, it would take half the time of the BA course to be qualify as a barrister in London. This qualification would secure Gandhi’s career in his hometown or in Bombay. This idea immediately possessed Gandhi.

Let us be reminded that it was the 19 century in India. At that time, orthodox Hindus had a panic about going abroad, especially the conservative community where Gandhi belonged. They feared to be casted off from their caste, and unable to find food that suits their strict diet. Obviously, his mother did not like the idea. None Gandhis before had left the country, even hardly the region. The Gandhi’s relatives opposed and convinced the young man to abandon his outrageous plan. Moreover, his family, though being well-to-do, did not have the money to fund this expensive British education. Worst of all, the head of the caste, having heard of Gandhi’s endeavor, threatened to excommunicate him should he insist on the journey, and to fine anyone who spoke to him or went to send him off. Society, community, family, none supported him.

Nevertheless, all objections and hurdles had no effect on Mohandas Gandhi. He swore to his mother to be faithful with his wife and honor the strict food taboos. He got his brother to support, and his mother to sell family jewelries to invest in his education. He endured the isolation and bullying from people in his community. And most of all, accepted the risk of being an outcaste.

This was a daring act. Very daring, when we realize this was the first time Gandhi went against the norms. What exactly motivated this act historian could not tell. However their guess is the travelogues of journeys to Europe and America he had read. And because he had little idea or passion about a career in law, we can say that Gandhi was guided by his curiosity, then presented itself as the desire to see the world. September 1888, 1 month before his 20th birthday, Mohandas Gandhi sailed for London.

A law student in London

the typical student life

The imperial, industrial and international city of London in 1888 was every bit different from Gandhi’s town Rajkot. Here, besides studying to become a barrister, for the first time, Gandhi was exposed to international friendship, community activities and journalism. The London chapter of his life was significant to his becoming the future leader of largest nation on earth.

Only that 20-year-old Mohandas Gandhi had no ambition whatsoever to be an important person. Gandhi was benign and naïve like a deer. Studying at home during the days, walking around the city, cooking his own meals to save money, sitting in his exams, sitting in extra exams because Indian liked to collect certificates, taking the dress code very seriously, dining in the obligatory dinners in which he kept his promise with his mother by applying for vegetarian meals and exchanging his wine for the fruit of his table-mates.

the London Vegetarian Society

This typical college student life would’ve continued without a happenstance: one day he saw on the street a copy of the book about vegetarianism; it dawn on him that there in London existed a community of vegetarians – the London Vegetarian Society. It ended up being Gandhi’s shelter in 3 years being in London.

If journeying to English was Gandhi’s peeking in the Pandora box, joining the London Vegetarian Society was to open it. Gandhi could have also ignored the Society to stay safe in his academic circle, or given a lurk-warm participation to focus on his expensive education. Instead, his integrity, curiosity, and conviction compelled him otherwise.

Gandhi’s integrity obliged him to keep the promise he made with his mother: to never touch meat or alcohol. However, vegetarianism was something Londoners found hard to swallow. Once Gandhi argued with an English doctor who exclaimed: “You must either take beef-tea or die!” He answer: “if it were God’s will that I should die I must die, but I was sure it could not be God’s will that I should break the oath that I made on my mother’s knee before I left India.” Besides, sport and theater – the 2 passions of Londoners – didn’t appeal to the visiting Indian student, nor did – ironically - imperial and social politics. The Vegetarian Society was something different.

He was curious and open enough to share rooms with a fellow from the Society. The Englishman and the Indian formed a friendship across racial divide. They threw vegetarian party in their flat and on some evenings at public places, they lectured together about the peace and health notion of vegetarianism. Other English friends introduced him to Theosophy, the concept of reconciling religions with science, and Christianity with Hinduism. This touched both his curiosity and humanity; thus Gandhi began his intensive studying of various religions.

His active participation in the Society - deliver lectures, attend conferences, write periodical essays for its newspaper – was motivated by Mohandas Gandhi’s belief about the humane ethos of vegetarianism: “it is not human life only that is lovable and sacred, but all innocent and beautiful life: the great republic of the future will not confine its beneficence to man,” as his favorite writer put it.

Gandhi’s random encounter with the London Vegetarian Society brought him a community of like-minded people. At first, an obsessed diet and spreading vegetarianism seemed to have nothing to do with his later fight for freedom, peace, and humanity. Nonetheless, though his membership he took crucial steps to become the Mahatma we all know: cultivate international friendships; organize community activities; study various religions; and express his opinions by writing.

An ineloquent lawyer in Natal

the unsuccessful early career

After 3 years in London, Gandhi the qualified barrister returned to India hoping to get a job in his region – which he failed to accomplish because of his brother’s dispute. He had no luck at the Bombay High Court either. “Often I could not follow the cases and dozed off,” Gandhi recalled, studying Indian law was “a tedious business.” Being a nonchalant speaker didn’t help with getting customers. The authorities of Gandhi’s caste still scorn him for travelling to London. Their contempt put an end to Gandhi’s dull hope in Bombay. After 10 months of little success in Bombay, Gandhi returned to his hometown Rajkot to set up a freelance office writing petitions and memorial. The income was modest, but for the first time in his life, Gandhi did not have to depend on loans from friends or family. This consoled him.

In 1893, 24 years old and 18 months of uninspired career, history brought Mohandas Gandhi an interesting opportunity: an Indian merchant in South Africa was in need of a lawyer who knew both his language and English; this merchant happened to know, of all the merchants in the region, Laxmidas Gandhi – brother of Mohandas Gandhi. The offer was decent and the prospect to become a lawyer was real. So in April, Gandhi sailed from Bombay again, this time for Natal.

Most Indian of Gandhi’s generation took their last breath in the same region where they took their first. Gandhi’s choice was exceptional and brave. Besides his desire to “see a new country…and have new experience,” Gandhi was left with no choice. He could have played smart, flattered and softened the authorities in Bombay. But Gandhi’s integrity did not allow him to compromise:

Everything depends upon one man who will try his best never to allow me to enter the caste. I am not so very sorry for myself as I am for the caste fellows who follow the authority of one man like a sheep. Is it not almost better not to have anything to do with such fellows than to fawn upon them and wheedle their fame so that I might be considered one of them?

Had Gandhi succeeded in the High Court, this choice of sailing across the world, leaving behind his wife and children, would have been daunting. Once again, life opened the door and Gandhi walked through it with curiosity, integrity and conviction at his back.

from lawyer to leader

South Africa was the perfect training ground for a future Mahatma, especially Natal – the British ruled region inhabited by most Indians. Few places in the world, even in India, existed such fierce racial conflicts and discrimination, here between the British ruling race and the ruled ones including Indian, African, Chinese. Gandhi arrived to Natal with the single-minded intention to help solving the Indian merchant’s case - an experience that might benefit his career upon his returning to India. But history had other plan for him.

the lawyer

It took 1 year for Mohandas Gandhi to solve the case for which he came to South Africa. In this year, he could have been a sensible lawyer who worked for his boss during weekdays and relaxed during weekends. However, Gandhi’s humanity couldn’t help but being throbbed with the everyday signs of inequity in Natal.

The incident that later became famous was Gandhi’s getting thrown out of a train in the 2nd week in South Africa, albeit having a valid first-class ticket, because of his color. This struck him that: “the hardship to which I was subjected was superficial – only a symptom of the deeper disease of color prejudice. I should try, if possible, to root out the disease and suffer hardships in the process.” Once when an unjust piece of news reached him, Gandhi couldn’t help but sending a reply to express his opposing thoughts to the editor.

Gandhi’s diligence, care, and fondness of writing prompted him to undertake a side project: writing a how-to book for Indian students who wished to have an education in London. Though it was never published in his lifetime, the book sharpened Gandhi’s writing craft and gave him something meaningful to work on. His curiosity and belief in reconciliation of religions enforced Gandhi’s further reading of Christian and Islamic texts.

What the 25 year-old Indian lawyer did in his spare time would later made him choose to walk through another open door.

the leader

As Gandhi had helped his client won the case, he was preparing to reunite with his homeland and family. Unexpectedly, in his own words, the “farewell party was turned into a working committee.” The Natal government had been increasing their pressure on the Indian community through new rules and restrictions. Now the Indian merchants offered him to stay. Gandhi agreed. He later recalled:

Thus God laid the foundations of my life in South Africa and sowed the seed of the flight for national self-respect.

Within 3 months after the decision to extend his stay in Natal, Gandhi, not year 25, was chosen to be the secretary of the newly-founded Natal Indian Congress.

It wasn’t Gandhi’s will to be drawn in racial politics. It was God’s will. What made Mohandas Gandhi different from millions of other Indians was his courage to say “Yes.” And his courage to hang-on.

“He was no orator… not eloquent, but rather otherwise…prefaced his speeches and comments by repeated sibilants, for instance: ‘Ess-ess-ess your worship, ess-ess-ess this poor woman… I ask ess-ess-ess that she should not be…, but cautioned ess-es-ess.’,” remarked one Court officer. Gandhi stammered as he spoke to defend for the rich, the middle class and the poor Indians in Natal. However people listen to both the lawyer Gandhi in the courtroom and the propagandist Gandhi in public meetings. Because his arguments were sound and his words carried conviction. To compensate for his indifferent speech, his writing was grip, direct and daring. Personal limits did not daunt him.

“I’m a regular goosie Gandhi, oh. With a talent that’s quite handy. And a pamphlet bash, that’s full. For this sunny-landy oh! I’ve a temper sweet as candy, oh. And a book and pencil handy, oh. You never saw such a social bore. As Goosie, Goosie, Gandhi, oh!” This is a part of the first poem about Gandhi, written when he was 27 in response to his first political and social pamphlet. The poem captures the hostility toward him among the British of Natal. This wasn’t some rare incident. His published work continuously caused uproar in the Natal public. Social humiliation did not shake him.

“He is not the man to lead a big movement. He has a weak face. He will certainly tamper with any funds he has the handling of. Such at any rate is my impression of the man – judging him by his face,” reported a white police informant on the subject. This informant made a great mistake. Blood was flowing down Gandhi’s “weak face” in the first physical attack he suffered in Natal at the age of 28. Nevertheless he did not bow, he took slow steps, steadily move through the terrific beatings that was raining on him. Violence did not stop him.

Gandhi quiet strength was manifested from his integrity and humanitarian conviction. The benevolent Gandhi seldom imposed anything on others, but he held firm beliefs about what did it mean to be human. This was the one thing Gandhi would fight for.

“You gave us a lawyer, we gave you back a Mahatma.” The sentence was written by a South African to an Indian. What I like about this statement is that it brings forth the role of history in transforming Mohandas Gandhi to Mahatma Gandhi. This understanding doesn’t undermine the effort of Gandhi himself. To the contrary, it gives light to what makes Gandhi capable of leaving his legacy. I think it is very hard for a person to be content in an anonymous life that is simply good. It is even harder to listen to his inner voice and walk through open doors to strange worlds, with changeless principles at his back. That’s how Gandhi claimed his 20s.

Sometimes I entertained the thought that if Gandhi had been born at another place, in another time of history, he might have lived a simple anonymous life. Earning an honest living. Everyday taking joy in learning, writing and simple acts of kindness. Caring not about fame or wealth or power. A man of no ambition. A man with no pursuit other than to live in harmony with his conscience, other fellow beings and the earth. That’s exactly why nobody else was as qualified as Mohandas K. Gandhi when the world needed a Mahatma.

--- Gandhi before India by Ramachandra Guha was a thorough biography, written with much flair. It expands readers understanding of the first 45 years of Gandhi’s life. I’m much grateful to Guha and his book to be able to write this article.